Note: This was written largely on the evening of 11/27. It was edited on 11/28 to adjust for the changing situation, but most of the content remains from the original version.

Historian, economist, and erstwhile commentator Adam Tooze is fond of the term, polycrisis, which he defines as “not just a situation where you face multiple crises,” but “where the whole is even more dangerous than the sum of the parts.”

China is facing just such a moment right now, and I think the next week will be a major inflection point—largely determining the course of 2023 and generating reverberations for the remainder of Xi’s third term.

I originally planned to merely summarize the current COVID situation and relay some dark COVID humor on Chinese social media, but events over the past 48-72 hours have gotten out of hand. Remarkable protest activity has interwoven with COVID policy, imposing formidable dilemmas on the top Chinese leadership.

Note that this is a moment of great uncertainty. This article constitutes my preliminary assessment of the situation, quickly cobbled together in one evening (and edited on a second evening). Obviously, the situation could and likely will change dynamically and rapidly. I will do my best to caveat my assessment appropriately throughout.

Mood Lighting

China’s national caseload began spiking around the end of October and in early November, mostly in Guangzhou in the south, Chongqing in the interior, and also to some degree elsewhere. In the process, we also saw interesting instances of disobedience against COVID policy, for instance by the Foxconn factory for iPhones in Zhengzhou.

Then, on November 11, the Chinese government released the “Twenty Measures” [二十条], to “further optimize” anti-epidemic controls, a long hoped for post 20th Party Congress adjustment. While the policy change was clearly limited, it also sent a signal in the direction of opening, for instance by no longer contact tracing “secondary” contacts (ie. contacts of contacts), allowing home quarantine rather than centralized quarantine for more types of contacts, and reducing quarantine time for arrivals from outside China from 7+3 (seven days at a hotel and three at home) to 5+3.

At the same time, COVID cases continued increasing rapidly in Guangzhou, remained high in Beijing (by Beijing’s standards, around 400 per day), and a number of cities halted COVID testing, spurring rumors (among Chinese, not just in Western media) that one such city, Shijiazhuang, was a “test case” for living with COVID or exiting COVID-zero. In fact, that would make a lot of sense for China, which has had a de facto practice of trialing major policies in “test” cities or provinces before rolling them out nationwide, such as the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone as China opened up to the outside world in the 1980s. The Chinese government could, in theory, seal off Shijiazhuang from the rest of the country, mobilize medical resources there, and see what happens when COVID transmits among that population before taking more drastic nationwide steps. With the national caseload reaching around 20,000 per day and increasing fast on November 15, it seemed like we might be reaching an end for COVID-zero. Beijing’s case is instructive. It had went to full remote work in the central business district (Chaoyang District) for more than a month over just about 40-80 daily COVID cases in May and June, but most people were still working largely normally in the office despite 400 daily cases—things had clearly changed.

Then, a (soft) hammer came down. Shijiazhuang re-introduced mass COVID testing and locked down segments of the population on November 20, while Beijing’s main business district shut down indoor dining and went largely to remote work on the same day. Beijing’s response has thus far been ineffectual, with cases increasing from 621 on November 19 to 4,307 on November 26. The government response has certainly been more lenient than earlier this year. Guangzhou is not in a full city-wide lockdown, only multiple districts, despite running at over 8,000 cases for the past 10 days. Beijing has not imposed any sort of even district-wide lockdown. So, we saw a backpedalling from the “20 Measures,” but not a complete repeat of previous policy.

Despite this, the social media sentiment (which I observed in my WeChat moments, akin to posts by Facebook friends) towards COVID policy became more sarcastic, despondent, and angry than any other time I have been in China, and I think even more so than during the Shanghai lockdown. The policy whiplash—excessive optimism over the government’s policy, followed by crushing of that hope—seemed to trigger a spree of negative or satircal posting. One critical event to add is a fire at an apartment in locked-down Urumqi which killed ten people on November 24, with some claiming that the building’s fire escapes were blocked and that fire trucks were delayed from responding as a result of zero-COVID policy; this was just the latest tragedy that seemed self-induced by COVID and triggered outrage. Lastly, others have pointed out that seeing the World Cup proceed as normal has also generated disillusionment towards zero-COVID.

A Protest Taxonomy

By now, you have likely read of the recent protests against COVID policy in China. I think it is most helpful to disaggregate the protests into several different types.

Type One: The type I have seen the most direct documentation of is residential community-level [社区] protests against excessive local implementation of COVID-zero in Beijing. Some communities have created online sign up lists in WeChat to collectively resist transport of COVID-positive residents to makeshift hospitals (方舱), which have awful conditions, and to instead be permitted to stay in home isolation. Other remarkable videos have surfaced showing residents berating (aka negotiating very firmly with) their neighborhood committees (居委会, a grassroots party institution in every neighborhood) or arguing with police officers over the legality of community lockdowns, which neighborhood committees apparently lack despite being the frontline enforcers of zero-COVID. I have even see people share WeChat articles that provide instructions for communities on how to organize against unlawful lockdowns (see photo below for an example). This is truly a remarkable study in Beijinger resilience, but the scope of the protests is narrowly circumscribed—administrative pushback against the worst excesses of zero-COVID. I have seen this activity primarily in photos, videos, and articles shared in WeChat.

A screenshot of an article titled “What to do if your residential community has been locked down? This is an SOP.” It goes on to describe the circumstances in which lockdowns are illegal and how to combat them.

Type Two: A second type is student protests, seemingly mostly against restrictive COVID policies, but additionally to some degree expressing wider dissatisfaction with the government. These protests, which by some counts have occurred in at least 51 universities (I cannot independently verify this number, it was shared on WeChat) include ones at China’s most prestigious universities, Tsinghua and Peking University. It is hard to get good fidelity on the nature of these protests. At Tsinghua, I heard secondhand that Tsinghua Deputy Party Secretary Guo Yong met with the protesting students on Sunday, agreed to hold a larger discussion with students the next day, said students protesting would not be punished, and sang the national anthem and the Internationale with students. It was reportedly started somewhat spontaneously by a female student holding a blank sign in honor of the Urumqi fire victims. The meeting on Monday centered on practical student demands relating to COVID testing requirements, taking classes pass/fail, options to drop classes, etc., per attendees. On other campuses, it seems that there were some messages the government might find threatening shared on flyers, such as quoting from the Les Miserables song “Do you hear the people sing,” which was also used by Hong Kong protesters. Information in this paragraph comes largely from WeChat and a bit from Twitter, and is very far from comprehensive over the many universities that may have seen some activity.

Type Three: Multiple large-scale protests have reportedly occurred in other cities, but it is hard to get a good idea of what is actually going on, and I have seen little primary source content on Chinese social media. On the evening of November 26, people in Urumqi marched on the city government, seemingly to demand an end to the lockdown. There were also protests in Wuhan on November 27, which according to something I saw secondhand on WeChat has “not been as peaceful as Beijing.” Most remarkably, residents in Beijing gathered to mourn the Urumqi dead and protest against lockdowns on the evening of November 27. There had also been videos coming out from a couple weeks earlier of people tearing down COVID barricades in Guangzhou, and more recent clashes at Foxconn last week. It still seems like lots of this is spontaneous, though Wuhan, Urumqi, and Beijing may have been more planned. Unfortunately, most of my understanding comes from Twitter, so it is even harder for me to verify authenticity.

Type Four: There was one protest that openly called for a change in government. A vigil commemorating the Urumqi fire at Shanghai’s Wulumqi (Chinese transliteration of Urumqi) road in Xuhui district (not super central, but not in the suburbs) erupted into calls of “step down, CCP, step down, Xi Jinping” (or perhaps “down with the CCP, down with Xi Jinping”) [共产党 下台,习近平 下台]. This is extraordinary to see, to say the least, but who knows where it will go. Some people who participated have reportedly already been arrested (which would be unsurprising). Once again, my understanding only comes from Twitter.

Is it now or is it never?

Social scientist Timur Kuran used the phrase “Now out of Never” to describe how the 1989 Soviet bloc protests surprised the world, since if it seems like no one is willing to protest, then very few people are willing to put themselves out on a limb to protest. But if it seems like lots of people are willing to risk protesting, then suddenly more people are interested, which can create a positive feedback loop.

We are certainly seeing a positive feedback loop of some variety. Earlier this week, I had already thought the level of scorn being leveled at COVID policy in my WeChat moments was remarkable, but in the last 72 hours, that has turned into partially-organized actions. I posit that due to the extra pressure the protests place on the abundant contradictions between COVID and economic policy, the Chinese government will be forced to act in some way to resolve the dilemma.

China’s condition pre-protest was already fragile. Authorities could not figure out how to open up at acceptable cost, taking as one person put it, “one step forward, and ten steps back.” Some think that it is still possible to relax COVID policy gradually in coming weeks, but I think that remains near impossible to achieve given the infectioness of current Omicron variants. Practical policy over the past week has shown that the “Twenty Measures” could not be undertaken without infection rates taking off, and the Chinese leadership has yet to find an “acceptable” (to the leadership) path to living with the virus—admittedly a difficult task when the leadership has yet to ensure universal vaccine coverage, create an adequate stockpile of therapeutic drugs, or vastly expand hospital ICU capacity. However, I do think that my assessment that some new action must be taken is more of an assumption than a well-grounded assessment.

The protests will make it even harder for the government to find the path out. Protests make it harder to undertake the heavy handed COVID measures that do reduce caseload (despite extraordinary costs). Protests additionally trigger the natural antibodies in the party against internal threats, and swallow up other state resources that otherwise might be used in trying to combat the pandemic. I do not see this as a scenario where the government can allow protests to just continue for months, and it feels difficult for the protests to just peter out when they are directed against COVID-zero, which is the most difficult policy for the government to fundamentally change right now.

However, over the past 24 hours there have been some new indicators that the protests might simply peter out instead. First, students are being encouraged to return to their homes and leave campuses. For instance, Tsinghua is already setting up special free shuttle buses to take students to train stations or airports, more than a month before winter break. Since campus restrictions are a big source of frustration for students (some campuses have been locked down for lengthy stretches through COVID) and since this disrupts organization, student protests will peter out if this continues. There is a small chance this could seed student protesters across the country, where they could launch isolated protests, but I do not think that is likely. Second, police presence seems to have been beefed up in major cities, which seems to have deterred demonstrations. Third, censorship has been operating much more effectively in recent days, with many fewer photos, videos, and articles vaguely protest related appearing in my WeChat and with new articles appearing that provide a somewhat nuanced opposition to the large scale anti-regime protests but try to sympathize with protesters and get them to see things from the government’s point of view. Fourth, part of the outrage and some of the demonstrations were clearly linked to the Urumqi fire. It is unclear how quickly that event will fade from historical consciousness and whether the Type Three protests will continue without more vigils.

Therefore, I see three main choices available for the government (or COAs, courses of action).

COA 1: Lock down areas with high case loads and/or protests. Protests occur in part because residents can (ie. they have not yet been locked down) and COVID policies are nuanced enough right now to allow negotiation of finer points. The government could choose to lock down areas with higher caseloads, which would close off Type One protests, and could also lock down areas with high levels of protest activity, which would definitely make people madder, but it’s probably harder to organize collective action if everyone is stuck in their rooms. This COA would require mobilization of significant government capacity, and moderate to high coercion.

COA 2: Try to muddle along on COVID while only arresting a small proportion of protest participants (targeting “leaders” or “organizers”) and waiting for the protests to otherwise peter out. Perhaps the government thinks that it is better to still strike a middle balance on COVID policy, even if it is near impossible to balance this pendulum, and instead make examples out of a small number of protesters and protest leaders to decapitate any nascent organizations and deter future action. Type One protests may not require decapitation, Type Two might, and organized Type Three and Four likely would. If the government is unable to come to a decision on a major adjustment to COVID policy, this policy is most likely.

COA 3: Actually open up or announce a pathway to opening. Type Two and Type Three protesters are driven primarily by lack of clarity in COVID policy, and Type One protesters would likely be more willing to accede to extreme COVID policies if they thought there was a real point to it—though some other Type Ones might oppose full opening. Coercive means would probably be still necessary against Type Four protesters. Note that this does not require actually opening up, but I think part of the frustration is that there is no clear path and no benchmarks. Creating a credible plan and sticking to it would go a long way to assuaging frustration.

It is really hard to put any numbers on these outcomes. I do think that opening up, while my favored policy, is probably least likely. Muddling along feels perhaps most likely since people may be tempted to continue the status quo in a situation of high uncertainty and risks. And I should leave a high possibility of a policy apart from what I suggest. So maybe let’s say 20% chance for COA 1, 40% for COA 2, 15% for COA 3, and 25% for a different COA than mentioned. But, note that these are very low confidence forecasts.

What to watch for then? I would expect us to get some more definite sign from the November Politburo meeting. The Politburo meets every month and has yet to meet (or conclude their meeting, if it has already started) in November. I would be shocked if this is not the main topic of their meeting, and the key decision will probably be made here.

This really feels like a hinge moment, and some very momentous decisions will likely be made in the next week. Let us hope that everyone is safe and the Chinese government finds the courage to steer the ship of state towards smoother currents.

To add some levity, here are some amusing items shared on WeChat over the last week lampooning COVID policy.

The wonders of Chinese social media

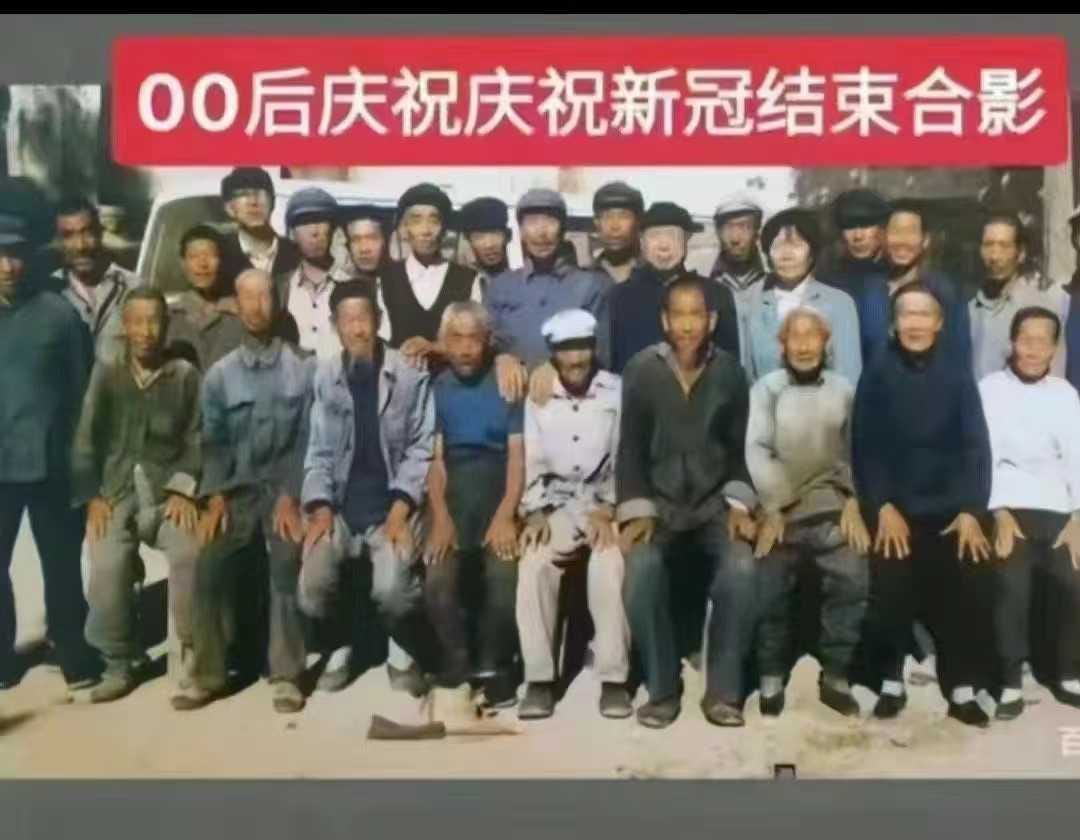

A photo captioned “00s generation (people born in the 2000s) group photo celebrating the conclusion of COVID”

Sometimes reality is more funny (but also depressing) than satire. An article on efforts for temporary COVID hospitals in Zhengzhou to improve their cultural offerings to that patients’ time being quarantined will be “a period difficult to forget in their life.”

An article that only says “支持,” or “support” to satirize the author’s position on COVID-zero. Similar articles were also shared saying just “好,” “good,” and something else I can no longer recall.

Another favorite was sharing videos or quotes of Chinese officials or leaders (including Xi, Xi’s dad, Mao, and Foreign Ministry spokespeople Zhao Lijian and Hu Chunhua) saying things about the importance of openness of speech, criticizing bad COVID policy in the US, or such, which the author clearly considered hypocritical. This Xi quote says “the Chinese people already have become organized, and if you piss them off, it is difficult to deal with.”